Chronophagy and Confetti: Reading Sonallah Ibrahim

‘The struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting.’

Milan Kundera, The Book of Laughter and Forgetting

When Brigadier Malcolm Dennison retired to his native Orkney in 1983, his erstwhile employer provided the transport: a C-130 Hercules, the largest aircraft ever to land at the islands’ airport. The plane was laden with seven tons of Dennison’s possessions – mainly books – accumulated during his 25 years working as an intelligence agent for two successive Sultans of Oman. (Seven tons wasn’t enough for Dennison. I knew him as a regular customer of the Stromness bookshop where I worked, buying ten or twenty books each time he visited.)

The first sultan to employ Dennison was Said bin Taimur, a ruler of medieval instincts, dedicated to personal wealth accumulation and the remorseless suppression of any dissent,and any moves to modernity. Among the 20th century evils he protected Omanis from were sunglasses, radios, medicine, and education. Under his regime there was just one primary school in the country, and reserved for the children of his closest staff.

In 1959 Dennison was involved in putting down a popular rebellion, and subsequently in organising an intelligence organisation to protect the interests of bin Taimur, as well as those of Oman’s real rulers, the British government. From 1892 to 1970, Muscat and Oman was a British ‘protected state’, neither a colony nor a protectorate, but something less visible. As Ian Gardiner, a Royal Marine posted there, wrote approvingly, ‘Arm twisting, threats, subsidies, and the occasional gunboat had secured stability on terms to the Imperial satisfaction without actually taking possession, and Oman remained nominally an independent state’ [1]

This arrangement allowed plausible deniability to the British, which they exploited repeatedly. In the mid-sixties, the United Nations passed a series of resolutions criticising Britain’s involvement in Oman. UN General Assembly Resolution 2073, XX, dated 17th December 1965, read ‘the colonial presence of the United Kingdom in its various forms prevents the people of the Territory from exercising their rights to self determination and independence.’ [2]

The UK attitude was to maintain that, as Lord Caradon wrote to the Foreign Office in 1966, ‘The Sultanate of Muscat and Oman is not a British colony’, and that, ‘there have been no attacks, no bombings, no repressions, no tortures, of any kind whatever.’ [3] The exact opposite of Caradon’s assertions was in fact the case; bombing, torture and repression of every kind being rained on Omanis for decades. But it wasn’t us! A big boy done it and ran away! The big boy being Britain’s puppet, Said bin Taimur.

This piling up of snippets of testimony from books, memoirs, documents, and letters is symptomatic of the contested history of Oman, as it is for many former colonies, protected states, dominions, and mandates. Independent archives are fragmented and precarious, if they exist at all. Official archives are partial in both senses of the word. Achille Mbembe has described the ‘chronophagy of the state’ [4] whereby powerful ruling bodies devour and destroy inconvenient historical documentation, obscuring their path to power and their means of retaining it. It's a theme Egyptian novelist Sonallah Ibrahim has returned to repeatedly in a long line of novels that are otherwise notable for their diversity. [5]

Ibrahim was born in Cairo in 1937 and spent all his life there. Apart from brief stays in East Berlin in the late ‘60s, when he worked as a journalist, and in Moscow in the early ‘70s, when he was enrolled on a film-making course, he rarely left Egypt. As a left-leaning youth, he took part in protests against the growing authoritarianism of President Gamal Abdel Nasser, which resulted in him being arrested on January 1st 1959 and thrown in jail, where he remained for five and a half years. While incarcerated, he suffered brutality amounting to torture, and saw friends led off to their death at the hands of the authorities.

The experience of imprisonment left its mark, and Ibrahim would return repeatedly in his books to the individual’s struggle for dignity – and life itself – in the face of oppressive political regimes. It was incarceration that convinced Ibrahim that he could better serve his ideals by being a writer rather than a political activist. The company of other imprisoned activists and intellectuals provided him with an intensive education in political and scientific theory, and in literature, with smuggled books by writers from around the world providing the fuel for intense discussions, firing the rest of Ibrahim’s career.

In 1964, Nasser, in an attempt to ingratiate himself with the Soviet Union, which was funding construction of the Aswan High dam, released Ibrahim and other Communist-sympathising prisoners. Ibrahim responded with his first book, a short novel, That Smell (1966), based on notes taken in prison and immediately after his release. The smell of the title was the stench of corruption – moral and political – that assaulted the narrator on his return to society. Its content shocked contemporary readers; its writing style was shocking too. He favoured a flat, affectless prose style, written in formal Arabic, but with the bluntness and straight-talking of urban speech:

I reached my hand towards her chest but she pushed it away and said, No. I rolled away, then stretched out beside her. I waited for her to turn and embrace me but she didn’t. I was awake. I felt the pain between my legs. I got up and went to the bathroom. I got rid of my desire, then came back and stretched out beside her. I slept and woke and slept again and when I opened my eyes it was morning and she had already put her clothes on. I’m leaving now, she said. [6]

Some literary figures, like Yusuf Idris, applauded its style, its pessimism, and its frankness about sex but others decried it. Yahya Haqqi called it ‘filth’. [7]

Unlike Idris and Haqqi and almost every other Egyptian writer of note in this period, Ibrahim refused to seek a government sinecure as an editor or civil servant. While the leading Arabic literary figure of the 20th century, Naguib Mahfouz, worked as a librarian, as a consultant to the Ministry of Culture, and even as the government’s Director of Film Censorship [8], Ibrahim made his modest living entirely from writing. This left him free to criticise and ridicule successive Egyptian regimes.

Ibrahim’s approach avoids the classic dramatic structures of realist fiction as brought to a kind of perfection in Mahfouz’s monumental Cairo Trilogy (1956 – 57.) Rather, the drama in his stories comes from the slow accumulation of small, repeated actions or details. The repetition at first seems tedious but eventually becomes powerful and, at times, terrifying. His approach has something in common with writers like James Kelman, or Karl Ove Knausgård, of whose books the critic James Wood said, ‘Even when I was bored I was interested.’ [9]

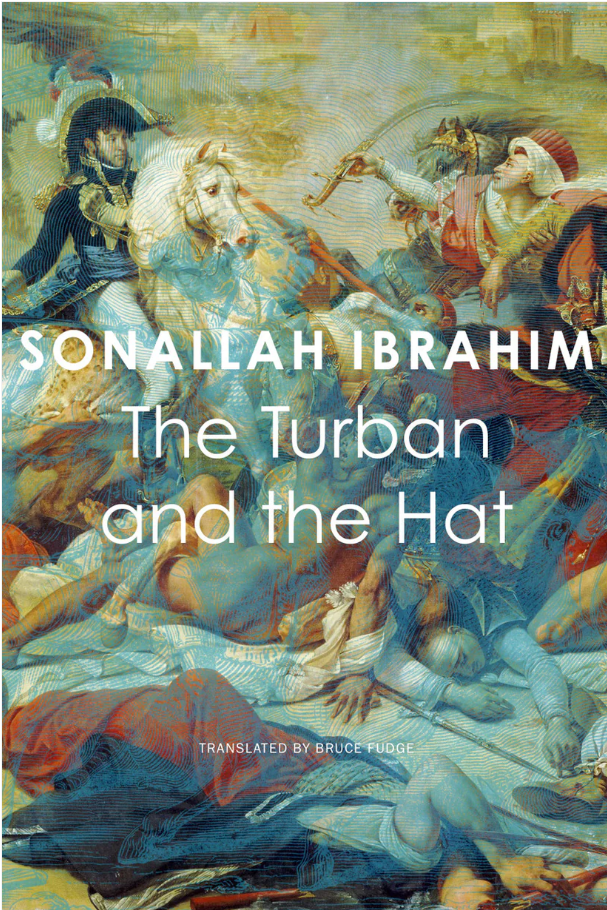

Most of Ibrahim’s books deal with the politics and culture of the Egypt he lived in, especially the repressive nature of successive governments, and the baleful effects of US influence in the Middle East. Sometimes the relationship to contemporary life is disguised, as in The Turban and the Hat (2008) for instance, an account of Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt and surrounding countries in 1798. It opens with a vivid scene:

I plunged into the seething crowd. The sun’s heat was stifling, and dust filled the air. I could feel the sweat streaming down my face and armpits. I stumbled on a mound of filth, all sweeping and cleaning having ceased since the French appeared on the outskirts of Cairo. I would have fallen had someone not grabbed my arm and pulled me up. My turban fell to the ground and unravelled. I picked it up and wrapped it back round my head. [10]

There we have the novel’s themes in a nutshell: the Napoleonic occupation of Cairo, the ensuing chaos, the threat to the complex, cosmopolitan culture of Egypt eventually seen off – at least for the moment. The hat threatens but the turban prevails. Parallels with US and European incursions into the Middle East in recent decades are unmissable.

The Committee (1981), on the other hand, is a funny, paranoid fable about a writer arrested for a crime which goes unspecified, but that he must defend himself against nonetheless. Its ending is one of the most shocking of any work of fiction. As with many of Ibrahim’s works, unwanted sexual activity (or the threat of it) often symbolises political action (or actual threat):

I turned around to see a strange sight: his pants bunched around his ankles and the rest of his body bare, Stubby was leaning over to pick up a big black revolver that had fallen to the floor.

He lifted the revolver with a quick movement and lodged it between his thighs, then pulled up his trousers […] I understood – and my heart beat violently – the secret of the bulge I had previously noticed between his thighs. This meant that I hadn’t been dreaming this morning when I imagined something firm bumping my thigh. I almost smiled when I saw that out of fear I had reversed the well-known Freudian axiom in which a gun is a symbol for the penis. [11]

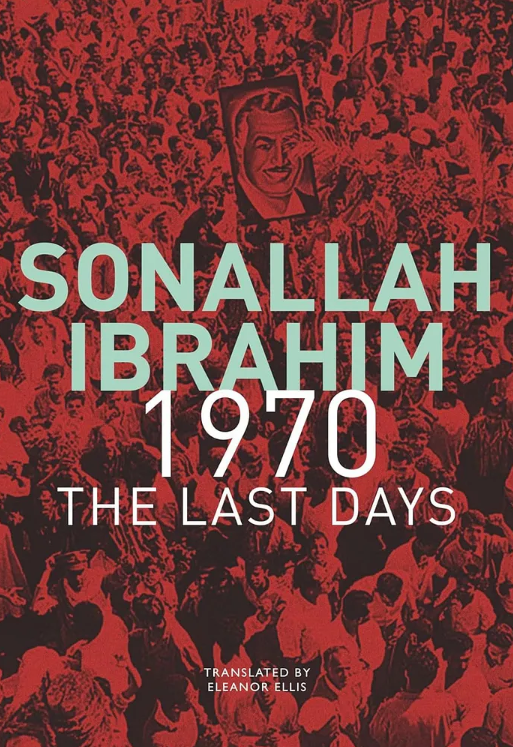

Back in what is clearly the ‘real’ world of the second half of the 20th century, Zaat (1992) follows the life of an ordinary Cairo woman through a maze of injustice and bureaucracy. Beirut, Beirut (1984) is narrated by a writer as he tries to find a publisher for his latest book in the liberal enclave of that city, where war and destruction is always in the recent past, or expected to return in the immediate future. Ice (2011) is suitably numb account of an Egyptian student supposedly studying film in 1970s Moscow, while anaesthetising his own psychic and political wounds with vodka and (unsuccessful) womanising. Stealth (2007) goes further back, to the narrator’s childhood, to record the experience of a boy struggling to understand his family and community through the partially successful means of spying on the adults around him. Ibrahim’s most recent novel, 1970: The Last Days (2020), follows Nasser’s movements in the months before his death. It’s narrated in the second person, ensuring simultaneous intimacy and alienation:

You sent Sadat, who was joined by Air Force officer Hosni Mubarak, to help Nimeiry deal with the Mahdist rebellion on Aba Island. Sadat wanted the Egyptian planes already deployed to hit them hard with airstrikes but you refused. The leader of the rebellion, al-Hadi al-Mahdi, was assassinated by explosives hidden in a basket of mangoes. [12]

Although I refer to the ‘real’ world, these books never offer simple realism. Often Ibrahim quotes headlines and even whole paragraphs from magazines and newspapers published at the time of his story. Films and TV news reports are similarly adduced or described. Everything he writes is fiction, but it’s fiction incorporating large chunks of reality, brought together to startling effect. For example, immediately following the sentences quoted, there are four headlines in a typeface distinct from that of the main narrative, and the following entry in Nasser’s diary is preceded by more:

In appearance this can result in pages that resemble those of John Dos Passos’s USA trilogy (1930 – 36) which also incorporates newspaper clippings, autobiography, and fictional narrative to create something more ‘real’ than realism. Whether Dos Passos was one of the writers Ibrahim read in prison is not recorded, but he did speak frequently of having encountered Ernest Hemingway’s work at this time, or at least descriptions of it. So perhaps Hemingway’s first book, In Our Time, was a model, with its short, blunt fictions interspersed with italicised entries that resemble excerpts from journalistic reports of ‘real life.’

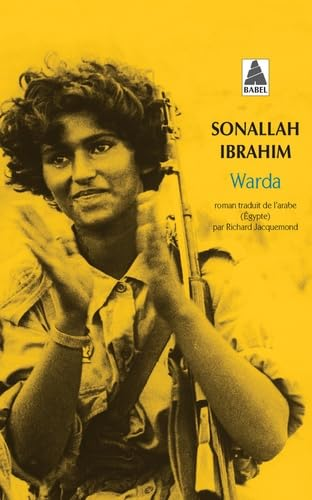

Nowhere is Ibrahim’s bricolage-like approach more powerful than in his greatest novel, Warda (2021.) Meaning ‘rose’ in Arabic, Warda is the code name of a young female fighter with an important role in the revolution in the southern Omani province of Dhofar in the1960s. This popular uprising, inspired by anti-colonialist struggles around the world, sought to overthrow the oppressive rule of the Sultans, and expel military and economic forces from the UK and elsewhere that both supported and exploited the Omani rulers. The story of the revolution, and Warda’s part in it, is told in two interweaving narratives. The first is the account by an Egyptian writer called Shukri, who travels to Oman many years after Warda’s disappearance (and the failure of the revolution) to try and track down any trace of her. The other is Warda’s own diaries from the 1960s and ‘70s, preserved by a supporter and passed on to Shukri under a cloak of secrecy; the current Sultan, Qaboos, son of Said bin Taimur, was no more likely to brook rebellion than his father. The diary sections are painfully gritty accounts of an armed struggle inspired by anti-colonialist, pan-Arabic idealism, which is gradually ground down by a combination of enemies with better technology and far greater resources, and the attrition of desert living with its ever-present natural dangers: disease, starvation, and terminal dehydration:

I awakened Dahmish before dawn. We raised up the camels as they spit and growled. We ate some dates without bothering to make tea or coffee. Then we headed towards the dunes. As we came closer, the sun started to fire up the sands. My camel gave a ferocious shiver. It refused to keep going. I felt dizzy and jumped off. My legs sunk into the sand up to the knee. With great effort, I pulled the camel behind me. My heart started to pound and my thirst became excruciating. […] Dahmish said we could do like the Bedouins: put a stick down the camel’s throat and drink its vomit. [14]

We, reading in the 21st century, know that the revolution, despite many short-term victories, was eventually defeated. Sultan Qaboos, with the aid of the SAS, overthrew his father, who retreated to exile in the Dorchester Hotel in London. Qaboos introduced a programme of modernisation, involving economic reforms and massive infrastructure projects. These were paid for largely by oil revenues received from the western oil companies he gave free rein to, with the labour being done by tightly controlled guest workers from India, Pakistan, and the Philippines. Qaboos’s attitude towards his own people could reasonably be described as one of repressive tolerance; many of his subjects became wealthy, all of them benefitted from the introduction of modern services such as bin Taimur had resisted, but all of them were also fully aware that their comfort came with the absolute requirement of obedience and even obeisance to Qaboos.

That kind of deference is no easier for Shukri to maintain in Oman than it was for Ibrahim in Egypt. Shukri pursues every possible trace of Warda, putting himself and those he persuades to help him, in danger of deportation or worse. The search for scraps of information and memory is thrilling, and the occasional appearance of further pages of Warda’s wartime diary provides passages of real excitement. They also provide moments of elation, as Warda recounts her idealism bearing fruit in the liberation of previously oppressed women and girls, or in the small victories over government forces in ambushes and skirmishes. There is great pathos too, as the 21st century reader knows that her revolutionary aspirations will eventually be crushed. In her final diary entries, as Warda attempts to escape her pursuers by crossing the unforgiving desert known as the Empty Quarter, she insists on seeing glimmers of hope for both herself and her mission. We see only impending tragedy.

The final volume of Warda’s diary, the one containing details of the final stages of her walk across the Empty Quarter, and where she ended up, does not appear till the last page of the novel when it is laid in front of Shukri by Warda’s brother, Yaarib. Once a youthful revolutionary himself, Yaarib is now a high ranking official in Qaboos’s government, and has, it seems, been secretly monitoring Shukri throughout his time in Oman. Warda’s diary risks unsettling the government’s official narrative; it makes clear the Dhofar revolution was more than a little local difficulty, but rather a challenge to the very nature of the state and its western backers. Yaarib must unleash some chronophagy:

Suddenly, he grabbed the journal with both hands and started ripping its pages into small pieces. We both stared at the paper scraps, piled now on the desktop like so much black and white confetti. [15]

1992: Warda’s slim but incendiary testament is destroyed. 1983: Malcolm Dennison’s seven tons of books are flown into Orkney. Had he read all of them? Impossible to say. Did he read he 10 or 20 books he bought per week, from the Orkney bookshop I worked in? That would have been physically impossible. My feeling is that he was building a wall of books around himself – but to protect himself from what? Again, impossible to say. All that can be said for sure is: to the victor the spoils, to the victor the books, the diaries, the memos, the maps, the photos, the archives, the proof, the evidence. To the victor a C-130 to fly it all home in. After a distinguished career with the RAF, Dennison had become an intelligence officer in Oman, working first for bin Taimur and then with Qaboos. A large part of his career involved suppressing rebellions such as the one Warda worked to foment. He doesn’t appear in Warda, but the work of the sultans’ intelligence operatives are everywhere, just as the work of the intelligence systems Dennison created are everywhere still in the ‘real’ Oman. There’s no doubt that Dennison was a victor, as was Qaboos. But what of Warda? She was not a victor politically or militarily, so must have been a loser. But Sonallah Ibrahim has ensured that she – and her real-life counterparts – will not be forgotten. He has rescued them from the jaws of chronophagy.

Sonallah Ibrahim died of pneumonia, aged 88, on August 13th 2025, as I was completing this essay. He was predeceased by his wife and is survived by one stepdaughter. Nine of his novels are available in English, with another, Star of August, due out in 2026. It’s an account of the building of the Aswan High dam, the dam that released him from prison and started his writing career.

Duncan McLean is a Scottish novelist, short story writer, playwright, and editor.

-

[1] Fergusson, Ron. ‘Obituary: Malcolm Dennison’, The Herald (Glasgow, 5th September 1996), p.12.

[2] United Nations, General Assembly Resolution 2073 (XX), Question of Oman, 17th December 1965 <https://docs.un.org/en/A/RES/2073(XX)> accessed 18th January 2026.

[3] Takriti, Abdel Razzaq. Monsoon Revolution: Republicans, Sultans, and Empires in Oman, 1963 – 1976 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), p.81.

[4] Mbembe, Achille. ‘The Power of the Archive and its Limits,’ tr. Judith Inggs, in Hamilton, Caroline et al, Refiguring the Archive (Dordrecht, Boston, London, Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2002), p. 23

[5] By far the most important survey in English of Ibrahim’s work is Paul Starkey’s Sonallah Ibrahim: Rebel with a Pen (Edinburgh, 2016.) Otherwise, coverage is restricted to chapters or essays in broader studies of Arabic literature or academic journals, reviews, general journalism, and, as of 2025, obituaries. I have listed those I found most useful in the bibliography.

[6] Ibrahim, Sonallah. That Smell and Notes from Prison, tr. Robyn Cresswell (New York: New Directions, 2013)

[7] Mehrez, Samia. Egyptian Writers between History and Fiction: Essays on Naguib Mahfouz, Sonallah Ibrahim, and Gamal al-Ghitani (Cairo and New York, The American University in Cairo Press, 1994), p. 41, 44.

[8] El-Enany, Rasheed. Naguib Mahfouz: His Life and Times, (Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press, 2007).

[9] Wood, James. ‘Total recall,’ The New Yorker , August 6th 2012 <https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2012/08/13/total-recall> accessed 18th January 2026.

[10] Ibrahim, Sonallah. The Turban and the Hat, tr. Bruce Fudge (London, New York, Calcutta: Seagull Books, 2022) p3.

[11] Ibrahim, Sonallah. The Committee, tr. Mary St. Germain and Charlene Constable (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2001), p103 – 104.

[12] Ibrahim, Sonallah. 1970: The Last Days, tr. Eleanor Ellis (London, New York, Calcutta: Seagull Books, 2024), p.76.

[13] Ibid., p.77.

[14] Ibrahim, Sonallah. Warda, tr. Hosam Aboul-Ela (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2021) p.322.

[15]Ibid., p358.

-

Works by Sonallah Ibrahim

Publication dates shown are those of the English translations referred to or quoted. For the dates of the original publications in Arabic, see Starkey (2017.)

1970: The Last Days, tr. Eleanor Ellis (London, New York, Calcutta: Seagull Books, 2024)

Beirut, Beirut, tr. Chip Rossetti (Doha: Bloomsbury Qatar Foundation Publishing, 2014)

‘Cairo from Edge to Edge,’ tr. Samia Mehrez, in Cairo from Edge to Edge (Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press, 1998)

Ice, tr. Margaret Litvin (London, New York, Calcutta: Seagull Books, 2019)

Stealth, tr. Hosam Aboul-Ela (London: Aflame Books, 2009)

That Smell and Notes from Prison, tr. Robyn Cresswell (New York: New Directions, 2013)

The Committee, tr. Mary St. Germain and Charlene Constable (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2001)

The Smell of It and other stories, tr. Denys Johnson-Davies (London: Heinemann, 1971)

The Turban and the Hat, tr. Bruce Fudge (London, New York, Calcutta: Seagull Books, 2022)

Two Novels and Two Women, tr. Barbara Hess (Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2011)

Warda, tr. Hosam Aboul-Ela (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2021)

Zaat, tr. Anthony Calderbank (New York and Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press, 2004)

Other Works

Allen, Roger, The Arabic Novel: An Historical and Critical Introduction, Second Edition (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1995).

Allen, Roger, Selected Studies in Modern Arabic Narrative: History, Genre, Translation (Atlanta: Lockwood Press, 2019).

Allen, Roger, Hilary Kilpatrick and Ed de Moor (eds.), Love and Sexuality in Modern Arabic Literature (London: Saqui Books, 1995).

Creswell, Robyn, ‘Egyptian novelists at home and abroad,’ in Ellen Rosenbush, ed., Harper’s Magazine, February 2011 (New York: Harper’s, 2011), pp. 71 – 79.

Currey, James, Africa Writes Back: The African Writers Series & The Launch of African Literature (Oxford: James Currey, 2008)

Deheuvels, Luc, Barbara Michalak-Pilulska and Paul Starkey (eds.), Intertextuality in modern Arabic literature since 1967 (Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 2009).

El-Enany, Rasheed, Naguib Mahfouz: His Life and Times, (Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press, 2007).

Elsadda, Hoda, Gender, Nation and the Arabic Novel: Egypt 1892 – 2008 (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2012).

Fergusson, Ron, ‘Obituary: Malcolm Dennison’, The Herald (Glasgow, 5th September 1996)

Gardiner, Ian, In the Service of the Sultan: A First Hand Account of the Dhofar Insurgency (Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military, 2006).

Jacquemond, Richard, Conscience of the Nation: Writers, State and Society in Modern Egypt, tr. David Tresilian (Cairo and New York: The American University in Cairo Press, 2008).

Mbembe, Achille, ‘The Power of the Archive and its Limits,’ tr. Judith Inggs, in Hamilton, Caroline et al, Refiguring the Archive (Dordrecht, Boston, London, Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2002), pp19 – 26.

Mehrez, Samia, Egyptian Writers between History and Fiction: Essays on Naguib Mahfouz, Sonallah Ibrahim, and Gamal al-Ghitani (Cairo and New York, The American University in Cairo Press, 1994).

Mehrez, Samia (ed.), The Literary Life of Cairo: One Hundred Years in the Heart of the City (Cairo and New York, The American University in Cairo Press, 2016).

Raspberry, Vaughan, ‘Counterproxy: Sonallah Ibrahim’s Warda and the Revolution in Oman,’ in Nicholas Mathew and Elisa Tamarkin (eds.) Representations, Volume 163 Issue 1 (Oakland: University of California Press, 2023), pp. 100 – 115.

Salti, Ramzi M, ‘Feminism and Religion in Alifa Rifat’s Short Stories,’ in The International Fiction Review, Volume 18, Issue 2 (International Fiction Association, Fredericton, 1991), pp. 108 – 112.

Starkey, Paul, Modern Arabic Literature (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2006).

Starkey, Paul, Sonallah Ibrahim: Rebel with a Pen (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2017)

Takriti, Abdel Razzaq, Monsoon Revolution: Republicans, Sultans, and Empires in Oman, 1963 – 1976 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016).

United Nations, General Assembly Resolution 2073 (XX), Question of Oman, 17th December 1965, retrieved from https://docs.un.org/en/A/RES/2073(XX), downloaded 18th January 2026.)

Description text goes here